Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The terminology in current use for sexual function and dysfunction in women with pelvic floor disorders lacks uniformity, which leads to uncertainty, confusion, and unintended ambiguity. The terminology for the sexual health of women with pelvic floor dysfunction needs to be collated in a clinically-based consensus report.

Methods

This report combines the input of members of the Standardization and Terminology Committees of two International Organizations, the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA), and the International Continence Society (ICS), assisted at intervals by many external referees. Internal and external review was developed to exhaustively examine each definition, with decision-making by collective opinion (consensus). Importantly, this report is not meant to replace, but rather complement current terminology used in other fields for female sexual health and to clarify terms specific to women with pelvic floor dysfunction.

Results

A clinically based terminology report for sexual health in women with pelvic floor dysfunction encompassing over 100 separate definitions, has been developed. Key aims have been to make the terminology interpretable by practitioners, trainees, and researchers in female pelvic floor dysfunction. Interval review (5–10 years) is anticipated to keep the document updated and as widely acceptable as possible.

Conclusions

A consensus-based terminology report for female sexual health in women with pelvic floor dysfunction has been produced aimed at being a significant aid to clinical practice and a stimulus for research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The terminology in current use for sexual function and dysfunction in women with pelvic floor disorders lacks uniformity, which leads to uncertainty, confusion, and unintended ambiguity. Comprehensive and precise description will aid this situation, leading to more accurate reporting. For example, many definitions are used to describe dyspareunia; few are specific as to the location or etiology of the pain. Women may be treated for sexual complaints from a large array of providers including physicians, psychologists, psychiatrists, or sex therapists. While other fields have standardized terminology regarding diagnoses of sexual dysfunction in women without pelvic floor dysfunction, these diagnoses and descriptions do not include descriptions of conditions commonly encountered by the urogynecologist or others who treat women with pelvic floor disorders, such as coital incontinence. More standardized terminology would aid inter-disciplinary communication and understanding, as well as educate our providers on standardized terminology used in other fields.

Existing published reports document the importance of including the assessment of sexual function. For example, while Haylen et al. [1] offers definitions of symptoms, that document does not comment on how to further evaluate sexual function or incorporate it into the assessment of women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Assessment of how pelvic floor dysfunction treatment affects sexual health and how to measure changes in sexual health are important to the practice of urogynecology. Ideally, terminology should be consistent between practitioners who treat women with sexual dysfunction and those who treat pelvic floor disorders. Terminology presented in this document will align with current terminology documents and a literature terms analysis will be included in the process.

This report contains;

-

1.

Definitions of sexual function relevant to the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction and terminology developed to designate the anatomic location of the symptom.

-

2.

Terminology currently accepted as standard outside the field of urogynecology will be referenced, as these terms will allow urogynecologists to communicate effectively with other practitioners providing care to women with sexual dysfunction and pelvic floor disorders.

-

3.

Assessment of sexual dysfunction of women with pelvic floor disorders including the history and physical exam necessary to assess women reporting sexual difficulties which may or may not be related to their pelvic floor dysfunction including physical exam, imaging, nerve testing, as well as descriptions of how sexual dysfunction is related to other pelvic floor disorders, such as urinary and anal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

-

4.

Management of sexual dysfunction in women with pelvic floor disorders is described including conservative, surgical, and pharmacological management. Management of sexual dysfunction may be provided by different disciplines working in this field. Terminology related to the different types of therapy will be specified and distinguished. In addition, surgical and non-surgical management strategies are defined and described.

-

5.

The working group consisted of stakeholders in sexual function including urogynecologists, sex therapists and physiotherapists and the document was vetted through the wider membership of IUGA and ICS. The working group includes optimal methods of reporting sexual function research in women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Currently no single document collates all elements required for diagnoses in the area of female sexual function in women with pelvic floor dysfunction in a comprehensive way. This report includes a full outline of the terminology for all symptoms, signs, ordered clinical assessments, the imaging associated with those investigations, the most common diagnoses, and terminology for different conservative and surgical treatment modalities.

Like all the other joint IUGA-ICS female-specific terminology reports, every effort has been made to ensure this Report is:

-

1.

User-friendly: Able to be understood by all clinical and research users.

-

2.

Clinically-based: Symptoms, signs, and validated assessments/investigations are presented for use in forming workable diagnoses for sexual health and associated dysfunctions.

-

3.

Origin: Where a term’s existing definition (from one of multiple sources used) is deemed appropriate, that definition is included and duly referenced.

-

4.

Able to provide explanations: Where a specific explanation is deemed appropriate to explain a change from earlier definitions or to qualify the current definition, this will be included as an addendum to this paper (Footnote a,b,c…). Wherever possible, evidence-based medical principles have been followed. This Terminology Report is inherently and appropriately a definitional document, collating definitions of terms. Emphasis has been on comprehensively including those terms in current use in the relevant peer-reviewed literature. Our aim is to assist clinical practice, medical education, and research. Some new and revised terms have been included. Explanatory notes on definitions have been referred, where possible, to the “Footnotes” section.

Acknowledgement of these standards in written publications related to female pelvic floor dysfunction, should be indicated by a footnote to the section “Methods and Materials” or its equivalent, to read as follows: “Methods, definitions and units conform to the standards jointly recommended by the International Continence Society and the International Urogynecological Association, except where specifically noted.”

Overview of sexual function and dysfunction

Over 40% of women will experience a sexual problem over the course of their lifetime. A sexual complaint meets the criteria for a diagnosis when it results in personal distress or interpersonal difficulties. With regard to sexual complaints that reach the level of a diagnosable sexual disorder, recent epidemiologic surveys place the prevalence of diagnosable sexual disorders at approximately 8–12% [2].

Normal sexual function and models of sexual response

“Normal” sexual function can be determined using a variety of standards and is therefore difficult to define. Multiple models have been developed to describe normal or healthy sexual function. In 1966, Masters and Johnson proposed a linear model of sexual response based on their observations of the physiologic changes that occurred in men and women in a laboratory setting. Their model consisted of four stages: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. Subsequently, Kaplan and Lief independently modified this model to include the concept of desire as an essential component of the sexual response. Basson introduced an intimacy-based circular model to help explain the multifactorial nature of women’s sexual response and that desire is responsive as well as spontaneous. This model further allows for the overlap between desire and arousal and is ultimately the basis for the DSM 5 combined disorder, Female Sexual Interest, and Arousal Disorder (FSIAD).

Screening and diagnosis

Sexual concerns should be addressed routinely. Many women are hesitant to initiate discussions but still want their provider to open the dialog about sexual problems. When a provider opens this dialog, he/she acknowledges and prioritizes the role that sexual health plays in overall wellbeing. A variety of questionnaires can be used to help identify women who suffer from sexual problems. These questionnaires are a useful adjunct to the patient history and physical examination in the diagnosis of sexual disorders.

Once a sexual problem has been brought up and/or identified, it is important that it is adequately assessed. Though time is limited in the clinical setting, it is important to ask questions that help determine the true nature of problem. When the patient presents with low desire, a detailed description of her problem, including the onset, duration, and severity of her symptoms, should be obtained. Her level of distress should be determined. Open-ended questions allow the patient to provide information essential for accurate diagnosis and the development of an appropriate treatment plan. If there is not enough time to have a complete discussion, a return visit should be scheduled to specifically focus on her sexual concerns.

History and physical exam

A comprehensive medical and psychosocial history, preferably of both partners, is essential [3].

A completed medical history can identify conditions that contribute to her symptoms. The gynecologic history is also a vital component in the diagnosis. Components of the sexual history should include direct questions about sexual behavior, safe sex practices, and whether or not there is a history of sexual abuse. Sexual history taking should always be conducted in a culturally sensitive manner, taking account of the individual’s background and lifestyle, and status of the partner relationship. A history of current medications should be taken. It should be noted in what way the additional pelvic floor symptoms interfere with sexual function. Medications as antihypertensive agents (alpha blockers, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, antidiuretics) chemotherapeutics, drugs that act on the central nerve system and anti-androgens may interfere with sexual function [4]. A history and physical examination with special attention to atrophy, infections, scar tissue, and neoplasms should be performed. Motor and sensory neurological function should be assessed. Clinical signs of urinary and fecal incontinence should be noted and provocation tests such as a cough stress test performed. For women with pelvic neurological disease a detailed neurological genital exam is necessary, clarify light touch, pressure, pain, temperature sensation, anal and vaginal tone, voluntary contraction of vagina and anus as well as anal and bulbocavernosal reflexes [5]. Basic laboratory testing should be performed such as serum chemistry, complete blood count, and lipid profiles to identify vascular risk factor as hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and renal failure [4].

Pelvic floor disorders and sexual dysfunction

The effects of pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) including urinary (UI) and anal incontinence (AI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) on sexual function remain debatable with some studies showing no and others a negative impact [6,7,8]. This variability can be attributed partly to the fact that the populations studied, as well as the methodology and the type of questionnaires used, are different between the studies. These discordant findings can also be attributed to the complexity of human sexual function which is subject to a host of influences. Despite conflicting published data, in general most PFDs are thought to negatively affect sexual health. Pelvic floor symptoms have been shown to be associated with low sexual arousal, and infrequent orgasm and dyspareunia [7]. Up to 45% of the women with UI and/or lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) complain of sexual dysfunction with 34% reporting hypoactive sexual desire, 23% sexual arousal disorder, 11% orgasmic deficiency, and 44% sexual pain disorders (dyspareunia or non coital genital pain) [9]. Sexual function is related to women’s self-perceived body image and degree of bother from pelvic organ prolapse (POP) [10]. Genital body image and sexual health are related in women with stage 2 or greater POP [11,12,13] particularly in the domains of sexual desire and satisfaction. Women with anal incontinence (AI) have similar rates of sexual activity but poorer sexual function than women without [12, 14]. An estimated 16% to 25% of women with chronic pelvic pain experience dyspareunia often leading to sexual avoidance [15]. High pelvic floor muscle tone and sexual dysfunction are related [16]. In women with PFDs there is a positive association between pelvic floor strength and sexual activity and function [17].

Resolution of symptoms after successful treatment of PFDs often improves sexual function and/or women’s wellbeing as measured on pelvic floor condition specific measures. After surgery for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) sexual function was unchanged in 55.5% of women, improved in 31.9% and deteriorated in 13.1% [18]. The resolution of coital incontinence is closely correlated to patient’s degree of sexual satisfaction and preoperative coital incontinence has been suggested as a prognostic factor for improvement of sexual function after surgery [19]. Most women who undergo surgery for POP report unchanged sexual function [20].

Symptoms of sexual function specific to pelvic floor dysfunction

Symptom

Any morbid phenomenon or departure from the normal in structure, function, or sensation, experienced by the woman and indicative of disease or a health problem. Symptoms are either volunteered by, or elicited from the individual, or may be described by the individual’s caregiver [1]. Sexual symptoms may occur in combination with other pelvic floor symptoms such as urinary, fecal, or combined incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse (POP) or pelvic pain.

Vaginal symptoms

-

1.

Obstructed intercourse: Vaginal intercourse that is difficult or not possible due to obstruction by genital prolapse or shortened vagina or pathological conditions such as lichen planus or lichen sclerosis.

-

2.

Vaginal laxity: Feeling of vaginal looseness [1].

-

3.

Anorgasmia: Complaint of lack of orgasm; the persistent or recurrent difficulty, delay in or absence of attaining orgasm following sufficient sexual stimulation and arousal, which causes personal distress [3].

-

4.

Vaginal dryness (NEW): Complaint of reduced vaginal lubrication or lack of adequate moisture in the vagina.

Lower urinary tract sexual dysfunction symptoms

-

1.

Coital urinary incontinence: urinary incontinence occurring during or after vaginal intercourseFootnote 1

-

2.

Orgasmic urinary incontinence (NEW): urinary incontinence at orgasm

-

3.

Penetration urinary incontinence (NEW): urinary incontinence at penetration (penile, manual, or sexual device)

-

4.

Coital urinary urgency (NEW): Feeling of urgency to void during vaginal intercourse.

-

5.

Post coital LUT symptoms (NEW): Such as worsened urinary frequency or urgency, dysuria, suprapubic tenderness.

-

6.

Receptive urethral intercourse (NEW): Having a penis penetrating one’s urethra (urethral coitus).Footnote 2

Anorectal sexual dysfunction symptoms [28]

-

1.

Coital fecal (flatal) incontinence: Fecal (flatal) incontinence occurring with vaginal intercourse (see related definition “Coital fecal urgency”).

-

2.

Coital Fecal Urgency: Feeling of impending bowel action during vaginal intercourse.

-

3.

Anodyspareunia: Complaint of pain or discomfort associated with attempted or complete anal penetration [28].

-

4.

Anal laxity: Complaint of the feeling of a reduction in anal tone.

Prolapse specific symptoms

-

1.

Abstinence due to pelvic organ prolapse: Non engagement in sexual activity due to prolapse or associated symptoms.Footnote 3

-

2.

Vaginal wind (Flatus): Passage of air from vagina (usually accompanied by sound).

-

3.

Vaginal laxity: Feeling of vaginal looseness.Footnote 4

-

4.

Obstructed intercourse: vaginal intercourse is difficult or not possible due to obstruction by genital prolapse or shortened vagina or pathological conditions such as lichen planus or lichen sclerosis.

Pain symptoms

-

1.

Dyspareunia: Complaint of persistent or recurrent pain or discomfort associated with attempted or complete vaginal penetration [1].Footnote 5

-

2.

Superficial (Introital) dyspareunia: Complaint of pain or discomfort on vaginal entry or at the vaginal introitus.

-

3.

Deep dyspareunia: complaint of pain or discomfort on deeper penetration (mid or upper vagina)

-

4.

Vaginismus (NEW): recurrent or persistent spasm of vaginal musculature that interferes with vaginal penetration.Footnote 6

-

5.

Dyspareunia with penile vaginal movement: pain that is caused by and is dependent on penile movement.

-

6.

Vaginal dryness: Complaint of reduced vaginal lubrication or lack of adequate moisture in the vagina.Footnote 7

-

7.

Hypertonic pelvic floor muscle: A general increase in muscle tone that can be associated with either elevated contractile activity and/or passive stiffness in the muscle [4, 35].Footnote 8

-

8.

Non coital sexual pain (NEW): pain induced by non coital stimulation.Footnote 9

-

9.

Post coital pain (NEW): pain after intercourse such as vaginal burning sensation or pelvic pain.

-

10.

Vulvodynia: vulvar pain of at least 3 months’ duration, without clear identifiable cause, which may have potential associated factors [37].

Specific postoperative sexual dysfunction symptoms

-

1.

De novo sexual dysfunction symptoms (NEW): new onset sexual dysfunction symptoms (not previously reported before surgery)

-

2.

De novo dyspareunia (NEW): dyspareunia first reported after surgery or other interventions

-

3.

Shortened vagina (NEW): perception of a short vagina expressed by the woman or her partner

-

4.

Tight vagina (NEW):

-

Introital narrowing: vagina entry is difficult or impossible (penis or sexual device)

-

Vaginal narrowing: decreased vaginal caliber.

-

-

5.

Scarred vagina (NEW): perception by the partner of a “stiff” vagina or a foreign body (stitches, mesh exposure, mesh shrinkage) in the vagina

-

6.

Hispareunia: male partner pain with intercourse after female reconstructive surgery.Footnote 10

Other symptoms

-

1.

Decreased libido or sexual desire (NEW): Absent or diminished feelings of sexual interest or desire, absent sexual thoughts or fantasies, and a lack of responsive desire [1, 3]. Motivations (here defined as reasons/incentives) for attempting to become sexually aroused are scarce or absent. The lack of interest is considered to be beyond the normative lessening with lifecycle and relationship duration.

-

2.

Decreased arousal (NEW): Persistent or recurrent inability to achieve or maintain sexual excitement. This may be expressed as lack of excitement, lack of lubrication, lack of vaginal and clitoral engorgement, or lack of expression of other somatic responses [1, 3].Footnote 11

-

3.

Anorgasmia or difficulty in achieving orgasm (NEW): Lack of orgasm, markedly diminished intensity of orgasmic sensations or marked delay of orgasm from any kind of stimulation [1, 3].

Signs

Sign

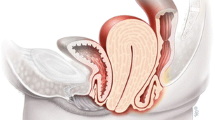

Any abnormality indicative of disease or health problem, discoverable on examination of the patient: an objective indication of disease or health problem [1]. Not all observed changes are associated with pathology from the point of view of the patient, and not all require intervention. The genital examination is often informative and in women with sexual dysfunction can often be therapeutic. A focused genital examination is highly recommended in presence of dyspareunia, vaginismus, neurological disease, genital arousal disorders, history of pelvic trauma, acquired or lifelong orgasmic disorder.Footnote 12 The internal examinations are generally best performed with the woman’s bladder empty [1]. Examination should be performed and described including vaginal length, caliber and mobility, presence of scarring and/or pain and estrogenization, and whether or not there is vaginal or labial agglutination. The location of any vaginal pain should be noted. Pelvic organ prolapse should be evaluated at it may influence sexual function by both affecting body image and vaginal symptoms during sexual activity [39]. If the patient has had an operation in which a synthetic mesh is utilized then mesh may be felt in the vagina which may or may not be associated with symptoms [40].Bimanual examination should be performed to make observations for any pelvic mass or unusual tenderness by vaginal examination together with suprapubic palpation. Examination of the pelvic floor muscles may elicit signs pertaining to female sexual dysfunction. If dyspareunia, vaginismus, or history of pelvic trauma are present, completing internal exams is difficult and may be impossible. Assessing for presence of vulvar pain via a gentle, introital palpation, or performing a “Q-tip touch test” of the introitus is recommended prior to any internal examination.

Perineal/vulval/urethral inspection and/or examination

-

1.

Vulval gaping: non-coaptation of vulva at rest, commonly associated with increased size of genital hiatus.

-

2.

Deficient perineum/cloacal-like defect: A spectrum of tissue loss from the perineal body and rectovaginal septum with variable appearance. There can be a common cavity made up of the anterior vagina and posterior rectal walls or just an extremely thin septum between the anorectum and vagina [28].

-

3.

Urethral: Prolapse, caruncle, diverticulum.

-

4.

Vulval agglutination: Labial lips fused.Footnote 13

Vaginal examination

-

1.

Vaginal agglutination: defined as condition where the walls of the vagina are fused together above the hymen.

-

2.

Vulvo-vaginal hypoesthesia: Reduced vulvo-vaginal sensitivity to touch, pressure, vibration, or temperature [4, 34, 35].Footnote 14

-

3.

Vulvo-vaginal hyperaesthesia: Increased vulvo-vaginal sensitivity to touch, pressure, vibration, or temperature

-

4.

Pudendal neuralgia: elicited or described by the patient as burning vaginal and vulva pain (anywhere between the anus and the clitoris) with tenderness over the course of the pudendal nerve [1].Footnote 15

Examination of pelvic floor muscles [ 1 ] ,

Footnote 16

-

1.

Muscle tone: In normally innervated skeletal muscle, tone is created by “active” (contractile) and “passive” (viscoelastic) components clinically determined by resistance of the tissue against stretching or passive movement [47, 48].

-

2.

Normal pelvic floor muscles: Pelvic floor muscles which can voluntarily and involuntarily contract and relax.

-

3.

Overactive pelvic floor muscles: Pelvic floor muscles which do not relax, or may even contract when relaxation is functionally needed, for example, during micturition or defecation.

-

4.

Underactive pelvic floor muscles: Pelvic floor muscles which cannot voluntarily contract when this is appropriate.

-

5.

Non-functioning pelvic floor muscles: Pelvic floor muscles where there is no voluntary action palpable.

-

6.

Pelvic floor muscle spasm or pelvic floor myalgia: defined as the presence of contracted, painful muscles on palpation and elevated resting pressures by vaginal manometry [49]. This persistent contraction of striated muscle cannot be released voluntarily. If the contraction is painful, this is usually described as a cramp. Pelvic floor myalgia (a symptom) may be present with or without a change in PFM tone (a sign).

-

7.

Pelvic floor muscle tenderness: occurrence of the sensation of pain or painful discomfort of the pelvic floor muscles elicited through palpation.

-

8.

Hypertonicity: A general increase in muscle tone that can be associated with either elevated contractile activity and/or passive stiffness in the muscle [47, 48, 50]. As the cause is often unknown the terms neurogenic hypertonicity and non-neurogenic hypertonicity are recommended.

-

9.

Hypotonicity: A general decrease in muscle tone that can be associated with either reduced contractile activity and/or passive stiffness in the muscle. As the cause is often unknown the terms neurogenic hypotonicity and non-neurogenic hypotonicity are recommended [48].

-

10.

Muscle strength: Force-generating capacity of a muscle [48, 51]. It is generally expressed as maximal voluntary contraction measurements and as the one- repetition maximum (1RM) for dynamic measurements [52, 53].

-

11.

Muscle endurance: The ability to sustain near maximal or maximal force, assessed by the time one is able to maintain a maximal static or isometric contraction, or ability to repeatedly develop near maximal or maximal force determined by assessing the maximum number of repetitions one can perform at a given percentage of 1 RM. [48, 54]

Urogenital aging (NEW): Genitourinary syndrome of menopause—(GSM) Footnote 17

,

Footnote 18

-

1.

Pallor/erythema: Pale or erythematous genital mucosa

-

2.

Loss of vaginal rugae: Vaginal rugae flush with the skin

-

3.

Tissue fragility/fissures: Genital mucosa that is easily broken or damaged

-

4.

Vaginal petechiae: A petechia, plural petechiae, is a small (1–2 mm) red or purple spot on the skin, caused by a minor bleed (from broken capillary blood vessels)

-

5.

Urethral mucosal prolapse: Urethral epithelium turned outside the lumen

-

6.

Loss of hymenal remnants: Absence of hymenal remnants

-

7.

Prominence of urethral meatus vaginal canal shortening and narrowing: Introital retraction

-

8.

Vaginal dryness: Complaint of reduced vaginal lubrication or lack of adequate moisture in the vagina.

General examination

Identify chronic systemic diseases and their treatments (eg, Diabetes, Multiple Sclerosis, Depression, Hypertension, lichen sclerosis) which can be associated with sexual dysfunction.

Neurological examination

For women with neurological disease affecting the pelvic nerves clarify light touch, pressure, pain, temperature sensation, and vaginal tone, voluntary tightening of the anus and vagina, anal and bulbocavernosal reflexes [57].

Investigations QOL; measurement of sexual function/health

While some physiologic measures of sexual activity and function exist, most are not readily available in the clinical or research setting, and many do not accurately reflect patient rating of improvement. Therefore, measurement of sexual activity and function is largely limited to self-report and the use of sexual diaries or event logs, clinician-administered interviews, or questionnaires. The US Food and Drug Administration drafted guidelines in 2016 which support the use of event logs and diaries as the primary measures for the evaluation of the efficacy of interventions. Further, they specified that diaries and event log should record “Sexually Satisfying Events (SSE)” and that the number of SSE’s may be used as a primary endpoint in efficacy trials. Unfortunately, these measures do not correlate well with patient report of improvement using other validated sexual function and quality of life measures [58]. Personal interviews are time consuming and have wide variation in application making the reliability of findings suspect.Table 1.

The FDA also recommended the use of patient reported outcomes for evaluation of sexual function. Most clinicians and researchers feel that questionnaires are the most accurate in measuring sexual function. Sexual function questionnaires include measures which were developed to include concepts important to women with pelvic floor dysfunction and those that were developed to address sexual health in women without pelvic floor dysfunction. In general, pelvic floor condition specific measures are more likely to be responsive to change than measures that are not condition specific, although both have been used in the evaluation of women with pelvic floor dysfunction. In addition, some questionnaires contain individual items or domains relevant to sexual function, such as the King’s Health Questionnaire, which has a domain specific to sexual function.

Increasingly, other measures, including those that evaluate body image, also impact sexual function and are associated with pelvic floor dysfunction. Measurement of these confounders may be important in order to assess the impact of pelvic floor dysfunction on sexual health.

Sexual diaries

A daily log of sexual thoughts, activities; supported by the US FDA as a primary outcome measure for the efficacy of interventions to evaluate sexual function.

Event logs

Record individual sexual events or activities. Each event is classified as a “sexually satisfying event (SSE)” or not. Event logs record individual events rather than activities on a daily basis.

Sexually satisfying event

This termed is coined by the US FDA, and is defined by the individual completing the questionnaire. The FDA stated that the term “satisfying” and what activities will be classified as a sexual encounter should be defined but did not supply a definition.

Questionnaires

Psychometric properties of some tools are reported in Table 1 [66].

-

1.

Pelvic Floor Condition specific sexual function measures: A validated sexual function measure which is developed to include concepts relevant women with pelvic floor dysfunction.

-

2.

Generic sexual function measures: A validated measure that was developed to evaluate sexual function but does not contain items relevant to pelvic floor dysfunction such as coital incontinence or vaginal looseness.

Investigations; measurement of physiologic changes

Physical investigations aim to evaluate different causes of sexual dysfunction and include investigations that focus on the vascular, neurologic, musculoskeletal, and hormonal systems. The clinical utility of these investigations in the routine assessment of female sexual health needs further validation. In many instances, these investigations are utilized in the research setting. Supplemental Table S1 reviews the validity and reliability testing of physiologic investigations.

Vascular assessment

Sexual arousal results in increased blood flow allowing genital engorgement, protrusion of the clitoris and augmented vaginal lubrication through secretion from the uterus and Bartholin’s glands and transudation of plasma from engorged vessels in the vaginal walls. Several instruments are available to measure blood flow during sexual stimulation [67, 68]. Inadequate vasculogenic response may be related to psychological factors as well as vascular compromise due to atherosclerosis, hormonal influence, trauma, or surgery.

-

1.

Vaginal photoplethysmography: A tampon shape intravaginal probe equipped with an incandescent light that projects toward the vaginal walls is inserted; the amount of light that reflects back to the photosensitive cell provides a measure of vaginal engorgement which can be expressed as vaginal blood volume or vaginal pulse amplitude depending on the mode of recording [69, 70]. Likewise, labial and clitoral photoplethysmography can also be evaluated [71, 72].

-

2.

Vaginal and clitoral duplex Doppler ultrasound: The anatomical integrity of clitoral structures and the changes in clitoral and labial diameter associated with sexual stimulation can be evaluated in B mode [73]. Movement of the blood relative to the transducer can be expressed as measurement of velocity, resistance, and pulsatility [74]. Blood flow in arteries irrigating the clitoris and the vagina are more commonly assessed during sexual stimulation [73, 75, 76].

-

3.

Laser Doppler imaging of genital blood flow: An imager positioned close to the vulva allows the assessment of skin/mucosae microcirculation at a depth of up to 2–3 mm [77]. This method has been used to assess response to sexual stimulation and correlated with subjective arousal [77]. It has also led to a better understanding of microvascular differences in women with provoked vestibulodynia compared to asymptomatic controls [78].

-

4.

Magnetic resonance of imaging of the genito-pelvic area: Evaluation of the increase in clitoral structure volume related to tissue engorgement occurring during arousal [78].

-

5.

Measurements of labial and vaginal oxygenation: A heated electrode and oxygen monitor are used to evaluate the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) transcutaneously [79, 80]. The temperature of the electrode is kept at a constant elevated temperature by an electric current. Increase in blood flow under the electrode results in more effective temperature dissipation (heat loss) with the result that more current is needed to maintain the electrode at its prefixed temperature. The changes in current provide an indirect measurement of blood flow during sexual stimuli [79, 80]. The electrode also monitors oxygen diffusion across the skin [79, 80].

-

6.

Labial thermistor: Temperature measurement evaluated with a small metal clip attached to the labia minora and equipped with a sensitive thermistor [81, 82].

-

7.

Thermography or thermal imaging of the genital area: Evaluation of genital temperature using a camera detecting infrared radiation from the skin during sexual stimulation [83]. This method has been correlated with subjective arousal [84].

Neurologic assessment

Related to intact sensation, neurological innervation is important for arousal and orgasm. Peripheral neuropathy or central nervous system disorders (eg, diabetic neuropathy, spinal cord injury) may lead to anorgasmia and decreased arousal [85,86,87]. Different approaches can be used to evaluate motor and sensory neurological function.

-

1.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging: Investigation of neural activation in anatomically localized cerebral regions evaluated through monitoring subtle changes in regional cerebral blood flow that occur with activation of the neurons. These patterns of activation and deactivation are used to examine the cerebral and cognitive response to sexual stimulation [88].

-

2.

Quantitative sensory testing: Assessment of the sensitivity by applying different stimuli (light touch, pressure, temperature, or vibration) using an ascending or descending method in order to evaluate the detection threshold. These methods can be used to evaluate different vulvo-vaginal sites including the clitoris, labia minora, and majora as well as vaginal and anal margins [85, 89, 90].

-

3.

Reflex examination: Evaluating sacral arc integrity, the bulbocavernous reflex can be elicited by squeezing the clitoris and assessing the contraction of the anal sphincter [91]. The external anal reflex is tested by repetitive pricking delivered to perianal skin and observing anal sphincter contraction [91]. Latencies can also be evaluated by stimulating the nerve and evaluating muscle response through a needle electrode [92].

Pelvic floor muscle assessment

Assessment of pelvic floor muscle (PFM) function involves evaluating the tone, strength, endurance, coordination, reflex activation during rises in intra-abdominal pressure as well as the capacity to properly relax this musculature. These muscles are involved in sexual function as PFM contraction occurs during arousal and intensifies with orgasm and PFM tone is related to vaginal sensation [93,94,95]. Superficial PFMs such as the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernous are also involved in erection of the clitoris by blocking the venous escape of blood from the dorsal vein [96]. Thus, reduction in PFM strength and endurance has been related to lower sexual function [97, 98]. Likewise, PFM hypotonicity may be related to vaginal hypoesthesia, anorgasmia, and urinary incontinence during intercourse [9] while hypertonicity may lead to dyspareunia [99, 100].

-

1.

Pelvic floor manometry: measurement of resting pressure or pressure rise generated during contraction of the PFMs using a manometer connected to a sensor which is inserted into the urethra, vagina, or rectum. Pelvic floor manometric tools measuring pressure in either mmHg, hPa, or cmH2O can be used to assess resting pressure, maximal squeeze pressure (strength), and endurance [101]. Details about recommendations to ensure validity of pressure measurements are provided elsewhere [101].

-

2.

Pelvic floor dynamometry: measurement of PFM resting and contractile forces using strain gauges mounted on a speculum (a dynamometer), which is inserted into the vagina [102,103,104]. Dynamometry measures force in Newton (N). Several parameters such as tone, strength, endurance, speed of contraction, and coordination can be evaluated [102,103,104].

-

3.

Pelvic floor electromyography (EMG): the recording of electrical potentials generated by the depolarization of PFM fibers. Intra-muscular EMG consists in the insertion of a wire or needle electrode into the muscle to record motor unit action potentials while surface EMG requires electrodes placed on the skin of the perineum or inside the urethra, vaginal, or rectum. EMG amplitude at rest and contraction can be recorded.

-

4.

Pelvic floor ultrasound imaging: evaluation of PFM morphology at rest, during maximal contraction and Valsalva. Several parameters pertaining to assess the bladder neck and anorectal positioning and hiatus dimensions can be measured [105,106,107].

Hormonal assessment

Hormones such as estrogen, progestin, and androgen influence sexual function and imbalance may lead to various symptoms including decreased libido, lack of arousal, vaginal dryness, and dyspareunia [108, 109]. Depending on the underlying suspected conditions associated with sexual dysfunction, hormonal investigations such as estradiol (or FSH if symptoms of deficiency), serum testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone acetate sulphate (DHEAS), free testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, prolactin, and thyroid function testing may be considered [110]. Moreover, the evaluation of vaginal pH and vaginal maturation index (ie, percentage of parabasal cells, intermediate cells, and superficial cells) can be helpful in women with vulvovaginal atrophy as it has been shown to be correlated with patient’s symptomatology [111].

Common diagnoses

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM-5), the International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10), and the Joint Terminology from the fourth International Consultation of Sexual Medicine (ICSM) all have proposed diagnoses for sexual disorders in women. Many of the diagnoses from the various societies overlap; we have chosen the diagnoses from the DSM 5, as well as the diagnosis of genitourinary syndrome of menopause as these diagnoses seem most relevant to the population of women with pelvic floor dysfunction, as shown in Table 2.

The DSM 5 has combined disorders that overlap in presentation and reduced the number of disorders from six to three. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and female sexual arousal disorders (FSAD) have been combined into one disorder, now called Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder (FSIAD), based on data suggesting that sexual response is not always a linear, uniform process, and that the distinction between certain phases, particularly desire and arousal, may be artificial. Although this revised classification has not been validated clinically and is controversial, it is the new adopted standardization. One reason offered for the new diagnostic name and criteria were clinical and experimental observations that sexual arousal and desire disorders typically co-occur in women and that women may therefore experience difficulties in both [112, 113].

The DSM-IV categories of vaginismus and dyspareunia have been combined to create “genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder” (GPPPD). Female Orgasmic Disorder remains its own diagnosis. The DSM 5 has also changed the relevant specifiers of these disorders with the goal of increasing objectivity and precision and to avoid over-diagnosis of transient sexual difficulties. In particular, all diagnoses now require a minimum duration of approximately 6 months and are further specified by severity.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is a new term introduced by the International Society of Sexual Medicine to describe a variety of symptoms which may be associated with sexual health. Although not validated, this diagnosis was introduced in an effort to improve communication between providers and patients regarding symptoms which may be difficult to discuss. While not a sexual dysfunction diagnosis, given the age of women who typically develop pelvic floor dysfunction, symptoms associated with GSM may be relevant to the assessment of the sexual health of women with pelvic floor dysfunction.

For each of the DSM-5 diagnoses, providers should indicate whether or not the condition is lifelong or acquired, generalized of situational, and rate the severity as mild, moderate or severe in terms of the distress it causes. All of the diagnoses, except for the pain diagnoses, need to meet the criterion that it has been present for 6 months, causes significant distress, and are not a consequence of non-sexual mental disorder, severe relationship distress and are not solely or primarily attributable to a medication or underlying illness [114]. For genitourinary syndrome of menopause, not all signs and symptoms need be present, but the symptoms must be bothersome and not better accounted for by another diagnosis [115].

Terms for conservative treatments

Lifestyle modification

Alterations of certain behaviors may improve sexual function. These include weight loss, appropriate sleep, adequate physical fitness, and management of mood disorders [116,117,118,119,120]. Vulvovaginal pain may be treated by dietary changes and perineal hygiene (avoiding irritant soaps, detergents, and douches), although data are conflicting [121]. Dietary modifications may be disorder specific including low oxalate diet as reduction in dietary levels of oxalate may improve symptoms of vulvodynia [122], or a bladder friendly diet with reductions in acidic foods and bladder irritants may treat bladder pain and associated sexual pain [123, 124].

Bibliotherapy

Use of selected books and videos to aid in treatment and reduce stress. Shown to improve sexual desire [125, 126].

Topical therapies

Lubricants and moisturizers-Application of vaginal lubricant during sexual activity or vaginal moisturizers as maintenance may assist with atrophic symptoms and dyspareunia [127,128,129]. Examples of some lubricants are described below, although no one lubricant or moisturizer has been adequately studied to recommend it over others. Additionally, not all products are available in all countries.

-

Essential arousal oil: Feminine massage oil applied to vulva prior to activity. Some evidence to support efficacy in treatment of sexual dysfunction, including arousal and orgasm, compared with placebo [130, 131].

-

Vulvar soothing cream: Non-hormonal cream containing cutaneous lysate, to be applied twice daily. Study shows improvement in vulvar pain with use compared to placebo [132, 133].

-

Prostaglandin E1 analogue, may help increase genital vasodilation. Ongoing trials to determine efficacy in arousal or orgasmic dysfunction [133,134,135].

Psychological intervention

Counseling and therapy are widely practiced treatments for female sexual dysfunction [116, 136]. Even when a sexual problem’s etiology and treatment is primarily urogenital, once a problem has developed there are typically psychological, sexual, relationship, and body image consequences and it may be tremendously validating and helpful for these women to be referred to counselors or therapists with expertise in sexual problems. Psychological interventions include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), sex therapy, and mindfulness training. While there is insufficient evidence with regard to controlled trials studying the efficacy of psychological treatment in women with sexual dysfunction, the available evidence suggests significant improvements in sexual function after intervention with traditional sex therapy and/or cognitive behavioral therapy.

Specific techniques include:

-

Sex therapy: Traditional treatment approach with aim to improve individual or couple’s sexual experiences and reduce anxiety related to sexual activity [116].

-

Cognitive-behavioral therapy: Incorporates sex therapy components but with larger emphasis on modification of thought patterns that may interfere with sexual pleasure [116].

-

Mindfulness: An ancient eastern practice with Buddhist roots. The practice of “relaxed wakefulness,” and “being in the moment,” has been found to be an effective component of psychological treatments for sexual dysfunction [137,138,139].

Non-pharmacologic treatments

-

Clitoral suction device: Non-pharmacological treatment, this is a battery-operated hand held device, designed to be placed over the clitoris. It provides a gentle adjustable vacuum suction with low-level vibratory sensation. Intended to be used three or more times a week for approximately 5 min at a time, this therapy has been shown to increase blood flow to the clitoral area as well as to the vagina and pelvis [119]. Small non-blinded studies have shown it may significantly improve arousal, orgasm, and overall satisfaction in patients with sexual arousal disorder [139, 140].

-

Vaginal dilators: Vaginal forms or inserts, dilators are medical devices of progressively increasing lengths or girths designed to reduce vaginal adhesions after pelvic malignancy treatments or in treatment of vulvar/vaginal pain [141, 142]. Can be useful for perineal pain or introital narrowing following pelvic reconstructive repairs, however, routine use after surgery not supported [143]. Dilators can also be used for pelvic floor muscle stretching (ie, Thiele massage) and was found helpful in women with interstitial cystitis and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunctions [144].

-

Vaginal vibrators, external and internal: May be associated with improved sexual function, data controversial [145, 146]. Possibility that use of vibrators for self-stimulation may negatively impact sexual function with partner related activity [147].

-

Vaginal exercising devices: Pelvic muscle strengthening tools in form of balls, inserts or biofeedback monitors. May improve pelvic floor muscle tone and coordination by improving ability to contract and relax. Studies are lacking assessing their use without concurrent physical therapy.

-

Fractional CO2 laser treatment: Use of thermoablative laser to vaginal mucosa may improve microscopic structure of epithelium [148,149,150]. This results in increased thickness, vascularity, and connective tissue remodeling, which can improve climacteric symptoms. Although long term data are lacking, some studies have shown significant improvements in subject symptoms of vaginal dryness, burning, itching, and dyspareunia as well as quality of life [149, 151, 152].

Alternative treatments

-

Acupuncture: Ancient Chinese practice that involves insertion of small needles into various points in the body in an effort to heal pain or treat disease. It may help with stress reduction, pelvic pain, and sexual dysfunction [124, 153, 154].

Physical therapy

Manual therapy: Techniques that include stretching, myofascial release, pressure, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, and massage applied externally on the perineum and internally to increase flexibility, release muscle tensions and trigger points in the pelvic floor muscles. It was found to be effective to improve sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders in recent meta-analysis and systematic review [17, 155, 156]. These therapies have also been found helpful in women with genito-pelvic pain [157].

-

•Pelvic muscle exercises with or without biofeedback: May improve sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders [156] or pain [124].

-

•Dry needling: Placement of needles without injection in myofascial trigger points [158].

-

•Trigger point injections

-

i.

Anesthetic: Injection of local anesthetics, often Lidocaine, directed by trigger point palpation, can be external or transvaginal [158,159,160].

-

ii.

Botox: Injection of Botulinum toxin type A, a potent muscle relaxant, into refractory myofascial trigger points to reduce pelvic pain [124, 158, 159].

Prescription treatments

Hormonal

-

Estrogen: Available via prescription for both systemic use (oral or transdermal preparations); or locally use (creams, rings, or tablets). May assist with overall well-being, sexual desire, arousal, and dyspareunia [119, 129, 161]. Role for topical use in treatment of post-surgical atrophy or mesh extrusion [162].

-

Ospemifene: Selective estrogen receptor modulator for treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia related to vulvar and vaginal atrophy, in postmenopausal women [163,164,165]. Acts as an estrogen agonist/antagonist with tissue selective effects in the endometrium

-

Testosterone: Not approved for use in women in the USA or UK, may be available in other countries. Variety of preparations including transdermal, oral, or pellet administration. Long term safety unknown, studies suggest improvements in satisfying sexual events, sexual desire, pleasure, arousal, orgasm, and decreased distress [116, 129, 135].

-

Tibolone: Synthetic steroid with estrogenic, progestogenic, and androgenic properties. It is not currently available in the USA. Studies have suggested a positive effect on sexual function with use [161].

-

Prasterone: dehydroepiandrosterone suppository available as a vaginal insert. It has been shown to be efficacious when compared to placebo in decreasing vulvovaginal atrophy [166].

Non hormonal

-

Bremelanotide; formerly PT-141- Melanocortin agonist, initially developed as a sunless tanning agent, utilizes a subcutaneous drug delivery system. Treatment significantly increased sexual arousal, sexual desire, and number of sexually satisfying events with associated decreased distress in premenopausal women with FSD [167].

-

Serotonin receptor agonist/antagonist; Flibanserin-5-hydroxytryptamine (HT)1A receptor agonist and 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, initially developed as antidepressant. Challenges in FDA applications, due to possible long term risks. Studies show improved sexual desire, satisfying sexual events, and reduced distress [168, 169].

-

Dual control model in differential drug treatments for hypoactive sexual desire disorder and female sexual arousal disorder:

-

i.

Testosterone in conjunction with phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (PDE-5)

-

ii.

Testosterone in conjunction with a 5-HT1A agonist

May be able to target physiologic and subjective measures of sexual functioning in a more specific manner. Premise of two types of HASDD subjects: low sensitivity to sexual cues, or prone to sexual inhibition. Tailoring on demand therapeutics to different underlying etiologies may be useful to treat common symptoms in women with lack of sexual interest and provide the appropriate therapy. Testosterone is supplied as a short acting agent 4 h prior to sexual event to lessen the side effect/risk profile [170,171,172,173].

-

Apomorphine: Nonselective dopamine agonist that may enhance response to stimuli [135, 174].

-

Antidepressants and Neuropathics: Include tricyclic antidepressants, and anticonvulsants, may be useful in treating sexual pain, and vulvar pain [122, 124].

-

Bupropion: Mild dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and acetylcholine receptor antagonist, it may improve desire and decrease distress or modulate Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) induced FSD [175].

Supplemental Table S2 presents studies evaluating the effect of various treatments on sexual dysfunction.

Surgery

The effect of pelvic reconstructive surgery for prolapse and incontinence on sexual health

Women with pelvic floor dysfunction commonly report impaired sexual function, which may be associated with the underlying pelvic floor disorder. Treatment of the underlying disorders may or may not impact sexual function [13]. While both urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse affect sexual function, prolapse is more likely than urinary incontinence to result in sexual inactivity. Prolapse is also more likely to be perceived by women as affecting sexual relations and overall sexual satisfaction. This perception is independent of diagnosis or therapy for urinary incontinence or prolapse [29, 176, 177]. Very little is known about the impact of fecal incontinence on sexual function [14]. The effect of pelvic reconstructive surgery on sexual function has increased but there is need for more focused research [30, 178]. Overall, randomized trials are lacking, varied outcome measures are used among studies [18]. There is a lack of reporting per DSM-IV/DSM 5 categories and a lack of long-term follow-up. Level of Evidence (LOE) is poor in many studies, and sexual dysfunction is usually reported as a secondary outcome measure. While any surgery can impact sexual function postoperatively, most commonly performed pelvic floor surgeries were not designed with the intent to improve sexual function. In general, successful surgical treatment of incontinence or prolapse may improve sexual symptoms associated with the underlying disorder. For example, coital incontinence improves after sling surgery, but whether it impacts other aspects of sexual function such as orgasm, desire, or arousal is unclear [18]. Surgery for prolapse may improve underlying symptoms of laxity or embarrassment from bulge, which in turn may improve sexual function, but does not seem to have a direct impact on other aspects of sexual function. A small but significant number of patients will develop pain or other sexual disorders following surgery. These pain disorders spring from a variety of causes including those caused by the use of grafts. Prediction of who will develop these pain disorders is challenging. A recent paper which evaluated the effect of vaginal surgery on sexual function reported that women overall reported improved function, decrease in dyspareunia rates, and that de novo dyspareunia rates were low at 5% at 12 months and 10% at 24 months [179]. Nonetheless, assessment of sexual activity and partner status and function prior to and following surgical treatment is essential in the evaluation of surgical outcomes. Because of the negative impact of pain on sexual function, assessment of sexual pain prior to and following procedures should also be undertaken.

Female genital cosmetic surgery

A number of surgeries have been developed that aim to improve sexual function by altering the appearance and/or the function of female genital tract. Evidence supporting the efficacy and safety of these procedures is lacking. In addition, standardized definitions of these procedures may help foster high quality research, standardization of technique, and outcome measurement in this field, but is currently lacking, and beyond the scope of this document. These procedures include, but are not limited to, labioplasty, vaginoplasty, laser vaginoplasty, perineoplasty, laser rejuvenation, clitoral de-hooding, labia majora augmentation, G spot amplification, laser treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy, and platelet risk plasma treatments.

Considerations for reporting in research

Sexual health should be included as an outcome for reporting research related to pelvic floor dysfunction; this is particularly important in the case of surgical interventions as adverse or advantageous sexual function outcomes would likely impact patient’s choice and satisfaction with interventions. The IUGA ICS Joint Report on terminology [39] for reporting outcomes of surgical procedures for POP described in detail items to be considered when reporting outcomes for prolapse surgical intervention [18]. De novo painful intercourse following prolapse surgery should be classified as described in these documents. While pain and its impact on sexual function is important, assessments limited to descriptions of sexual pain are not an adequate assessment of sexual health, and absence of pain should not be inferred to indicate that sexual function is intact or changed.

At a minimum, sexual activity status should be assessed. Assessment of sexual activity status should be self-defined and not limited to women who engage in sexual intercourse. In addition, it is important to not assume the gender of the woman’s partner. When reporting level of sexual activity, authors should report numbers of all patients who are sexually active (or inactive), with and without pain, pre- and post intervention.

In addition to sexual activity status, its associated level of bother should be documented. Use of validated patient reported outcome questionnaires to further assess the quality of sexual function should also be considered. These and other self-reported outcomes including sexually satisfying events and sexual diaries are described in Section 4, in this document. Assessment of the impact of pelvic floor disorder treatment on women’s sexual partners should also be considered. Conditions, among others, that commonly impact sexual function include hormonal status, body image, underlying medical conditions, and history of sexual abuse. Researchers may want to consider inclusion of these outcomes.

Limitations

This document includes a broad overview of terms important in the diagnosis and treatment of women with pelvic floor disorders. We have not included an in-depth description of all sexual disorders as this is beyond the scope of this document. Some disorders such as the persistent vulvar pain and vulvodynia are described elsewhere and we have tried to reference these documents as appropriate [37]. Not all management strategies presented are supported by robust evidence as to their efficacy; we have tried to include the data that supports interventions as it is available. In addition, there are ongoing debates regarding terms and diagnoses. For example, subsequent to the publication of the DSM-5, the International Consultation on Sexual Medicine (ICSM) in 2015 [180], and the International Society for Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) [181] published consensus papers on the nomenclature for female sexual dysfunctions. Based on the available evidence regarding clinical presentation, risk factors, and treatment response, both organizations recommended maintaining desire and arousal as distinct and separate clinical entities.

Notes

Coital incontinence is defined as a complaint of involuntary leakage of urine during or after coitus. Coital incontinence seems to be an aggravating factor that women generally describe as humiliating [1]. The prevalence of urinary incontinence during intercourse has been evaluated to range from 2% to 56%, depending on the study population (for eg, the general population or a cohort of women with incontinence), the definition used (any leakage, weekly, on penetration, during orgasm, only severe leakage) and the evaluation method used (questionnaire, interviews). In a literature review reported in 2002 that covered English-language papers from 1980 to 2001, Shaw [21] reported a 2–10% prevalence of coital incontinence in randomly selected community samples. The physio pathological mechanisms involved have been widely debated [22], with bladder overactivity conventionally being implicated in orgasmic incontinence and SUI in penetration incontinence. In the past 5 years, studies however, have underlined the role of the urethral sphincter in coital incontinence, which is thought to be crucial even in women with detrusor overactivity and orgasmic incontinence [23]. The penetration form of coital incontinence is largely associated with urodynamics findings of SUI, whereas orgasmic incontinence might be associated with both detrusor overactivity and SUI [23, 24]. Nevertheless, among women with OAB, orgasmic incontinence is more common than penetration incontinence. Coital incontinence on penetration can be cured by surgery in 80% of women with urodynamically proven SUI. Similarly, orgasmic incontinence can respond to treatment with anticholinergics in 59% of women with detrusor overactivity [25, 26].

Rare condition mostly described in women who have genital abnormalities such as micro perforate hymen [27].

A recent survey of IUGA members noted that 57% of responders considered vaginal laxity a bothersome condition that impacts relationship happiness and patient’s sexual functioning. The most frequently cited (52.6%) location responsible from laxity was the introitus and the majority of respondents (87%) thought both muscle and tissue changes were responsible [33].

Dyspareunia rates reported in the literature range from 14% to 18% [34].

There is often (phobic) avoidance and anticipation/fear/experience of pain, along with variable involuntary pelvic muscle contraction. Patients with vaginismus could present with severe fear avoidance without vulvar pain or fear avoidance with vulvar pain. Structural or other physical abnormalities must be ruled out/addressed [35]. There is controversy of whether or not this term should be retained; the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 2013 proposed to replace dyspareunia and vaginismus with the term “Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder (GPPPD).” [36]

Decreased vaginal lubrication is often involved in pain with sexual activity among postmenopausal women, women with hypo-estrogenic states for other reasons or after pelvic surgery and may result in persistent or recurrent vaginal burning sensation with intercourse (penile or any device) [4].

A non-relaxing pelvic floor that is mainly associated with dyspareunia. “Examination of pelvic floor muscles” section [8].

In certain disorders such as genital herpes, vestibulitis, endometriosis, or bladder pain syndrome, pain may also occur after non coital stimulation [4].

The term “Hispareunia” has been first suggested by Brubaker in one editorial to describe partner dyspareunia after sling insertion [38].

It has been suggested that a distinction could be made between women with sexual arousal concerns that are psychological or subjective in nature (ie, absence of or markedly diminished feelings of sexual arousal while vaginal lubrication or other signs of physical response still occur), those that are genital (impaired genital sexual arousal—reduction of the physical response), and those that include complaints of both decreased subjective and genital arousal [1, 4].

A normal examination is highly informative to the women and can be of reassurance value [4].

Other conditions that may influence sexual function are fissures, vulval excoriation, skin rashes, cysts, and other tumors, atrophic changes or lichen sclerosis, scars, sinuses, deformities, condylomata, papillomata, hematoma.

Increased blood flow in the vaginal walls associated with arousal increases the force in the vaginal walls, which drives transudation of NaCl+ − rich plasma through the vaginal epithelium, coalescing into the slippery film of vaginal lubrication and neutralizing the vagina’s usually acidic state [33]. Reduced vulvo-vaginal sensitivity has been associated with sexual dysfunction and neurologic impairment [34].

Sitting often exacerbates the pain, which may be relieved in the supine position. Presentation may be unilateral or bilateral in presentation.

Intra-vaginal or intra-rectal assessment palpation is useful to provide a subjective appreciation of the PFM. PFM tone can be evaluated and defined as hypotonic, normal, and hypertonic [41], or assessed using Reissing’s 7 point scale from −3 to +3 [42]. Squeeze pressure or strength during voluntary and reflex contraction can also be graded as strong, normal, weak, absent, or alternatively by using a validated grading system such as Brink’s scale or the PERFECT scheme [42,43,44]. These scales also include quotations of muscular endurance (ability to sustain maximal or near maximal force), repeatability (the number of times a contraction to maximal or near maximal force can be performed), duration, co-ordination, and displacement. Each side of the pelvic floor can also be assessed separately to allow for any unilateral defects and asymmetry [42]. Voluntary muscle relaxation can be graded as absent, partial, complete, delayed [42]. The presence of major morphological abnormalities of the puborectalis muscle may be assessed for by palpating its insertion on the inferior aspect of the os pubis. If the muscle is absent 2–3 cm lateral to the urethra, that is, if the bony surface of the os pubis can be palpated as devoid of muscle, an “avulsion injury” of the puborectalis muscle is likely [45]. Tenderness can be scored during a digital rectal (or vaginal) examination of levator ani, piriformis and internal obturator muscles bilaterally, according to each subject’s reactions: 0, no pain; 1, painful discomfort; 2, intense pain; with a maximum total score of 12 [46].

GSM is a syndrome associated with aging that results in alkalization of vaginal pH, changes in the vaginal flora, increased parabasal cell on maturation index and decreased superficial cells on wet mount or maturation index. In addition, there is a loss of collagen, adipose, and water-retention of the vulva which results in loss of elasticity, generalized reduction in blood perfusion of the genitalia. The vaginal epithelium may become friable with petechiae, ulcerations, and bleeding after minimal trauma [48].

Two classification systems for complications following prolapse surgery, includes the more generic Modified Clavien Dindo [55] and the more specific IUGA ICS classification of complications related to insertion of grafts/prosthesis [40] or use of native tissue [56]. These classification systems did include pain related to prolapse surgery complications which was sub-classified depending on whether pain was at rest, provoked during examination, during sexual activities, physical activities, or spontaneous

References

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, et al. An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:5–26.

Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segretti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970–97.

Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163:888–93.

Rupesh R, Pahlajani G, Khan S, Gupta S, Agarwal A, Zippe CD. Female sexual dysfunction: classification, pathophysiology and management. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:1273–84.

Basson R, Althof S, Davis S, Fugl-Meyer K, Goldstein I, Leiblum S, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J Sex Med. 2004;1:24–34.

Fashokun TB, Harvie HS, Schimpf MO, et al. Sexual activity and function in women with and without pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:91–7.

Handa VL, Cundiff G, Chang HH, Helzlsouer KJ. Female sexual function and pelvic floor disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1045–52.

Rogers RG. Sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:S199–201.

Salonia A, Zanni G, Nappi RE, Briganti A, Dehò F, Fabbri F, et al. Sexual dysfunction is common in women with lower urinary tract symptoms and urinary incontinence: results of a cross-sectional study. Eur Urol. 2004;45:642–8.

Lowenstein L, Gamble T, Sanses TV, van Raalte H, Carberry C, Jakus S, et al. Sexual function is related to body image perception in women with pelvic organ prolapse. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2286–91.

Jelovsek JE, Barber MD. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1455–61.

Zielinski R, Miller J, Low LK, Sampselle C, DeLancey JO. The relationship between pelvic organ prolapse, genital body image, and sexual health. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:1145–8.

Lowenstein L, Pierce K, Pauls R. Urogynecology and sexual function research. How are we doing? J Sex Med. 2009;6:199–204.

Cichowski SB, Komesu YM, Dunivan GC, Rogers RG. The association between fecal incontinence and sexual activity and function in women attending a tertiary referral center. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1489–94.

Kingsberg SA, Knudson G. Female sexual disorders: assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. CNS Spectr. 2011;16:49–62.

Bortolami A, Vanti C, Banchelli F, Gruccione AA, Pillastrini P. Relationship between female pelvic floor dysfunction and sexual dysfunction: an observational study. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1233–41.

Kanter G, Rogers RG, Pauls RN, Kammerer-Doak D, Thakar R. A strong pelvic floor is associated with higher rates of sexual activity in women with pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:991–6.

Jha S, Ammenbal M, Metwally M. Impact of incontinence surgery on sexual function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2012;9:34–43.

Lonnee-Hoffmann RA, Salvesen O, Morkved S, Schei B. What predicts improvement of sexual function after pelvic floor surgery? A follow-up study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:1304–12.

Jha S, Gray T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:321–7.

Shaw C. A systematic review of the literature on the prevalence of sexual impairment in women with urinary incontinence and the prevalence of urinary leakage during sexual activity. Eur Urol. 2002;42:432–40.

Serati M, Salvatore S, Cattoni E, Siesto G, Soligo M, Braga A, et al. Female urinary incontinence at orgasm: a possible marker of a more severe form of detrusor overactivity. Can ultrasound measurement of bladder wall thickness explain it? J Sex Med. 2011;8:1710–6.

El-Azab AS, Yousef HA, Seifeldein GS. Coital incontinence: relation to detrusor overactivity and stress incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:520–4.

Pastor Z. Female ejaculation orgasm vs. coital incontinence: a systematic review. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1682–91.

Serati M, Cattoni E, Braga A, Siesto G, Salvatore S. Coital incontinence: relation to detrusor overactivity and stress incontinence. A controversial topic. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:1415.

Serati M, Salvatore S, Uccella S, Cromi A, Khullar V, Cardozo L, et al. Urinary incontinence at orgasm: relation to detrusor overactivity and treatment efficacy. Eur Urol. 2008;54:911–5.

Di Denato V, Manci N, Palaia I, et al. Urethral coitus in a patient with a microperforate hymen. JMIG. 2008;15:642–3.

Sultan AH, Monga A, Lee J, et al. An international Urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female anorectal dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;28:5–31.

Barber MD, Visco AG, Wyman JF, Fantl JA, Bump RC. Sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:281–9.

Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR. Sexual function and vaginal anatomy in women before and after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1610–5.

Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet. 2007;369:1027–38.

Weber AM, Walters MD, Schover LR, Mitchinson A. Sexual function in women with uterovaginal prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:483–7.

Pauls RN, Fellner AN, Davila GW. Vaginal laxity: a poorly understood quality of life problem; a survey of physician members of the international Urogynecological association (IUGA). Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:1435–48.

Spector IP, Carey MP. Incidence and prevalence of the sexual dysfunctions: a critical review of the empirical literature. Arch Sex Behav. 1990;19:389–408.

Basson R, Leiblum S, Brotto L, Derogatis L, Fourcroy J, Fugl-Meyer K, et al. Revised definitions of women’s sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1:40–8.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: Author; 2013.

Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, Bergeron S, Pukall C, Zolnoun D, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS consensus terminology and classification of persistent vulvar pain and vulvodynia. J Sex Med. 2016;13:607–12.

Brubaker L. Editorial: partner dyspareunia (Hispareunia). Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:311.

Toozs-Hobson P, Freeman R, Barber M, Maher C, Haylen B, Athanasiou S, et al. International Urogynecological association, international continence society. An international Urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for reporting outcomes of surgical procedures for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:527–35.

Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Cosson M, Davila GW, Deprest J, et al. An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of protheses (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:3–15.

Devreese A, Staes F, De Weerdt W, et al. Clinical evaluation of pelvic floor muscle function in continent and incontinent women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:190–7.

Reissing ED, Brown C, Lord MJ, Binik YM, Khalifé S. Pelvic floor muscle functioning in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;26:107–13.

Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, Bø K, Corcos J, Fowler C, et al. Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: report from the pelvic floor clinical assessment Group of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:374–80.

Laycock J, Jerwood D. Pelvic floor muscle assessment: the PERFECT scheme. Physiotherapy. 2001;87:631–42.

Brink CA, Wells TJ, Sampselle CM, Taillie ER, Mayer R. A digital test for pelvic muscle strength in women with urinary incontinence. Nurs Res. 1994;43:352–6.

Dietz HP, Moegni F, Shek KL. Diagnosis of levator avulsion injury: a comparison of three methods. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40:693–8.

Simons DG, Mense S. Understanding and measurement of muscle tone as related to clinical muscle pain. Pain. 1998;75:1–17.

Bo K, Frawley H, Haylen B, et al. International (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the conservative and non-pharmacological management of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:191–213.

Montenegro ML, Mateus-Vasconcelos EC, Rosa e Silva JC, Nogueira AA, Dos Reis FJ, Poli Neto OB. Importance of pelvic muscle tenderness evaluation in women with chronic pelvic pain. Pain Med. 2010;11:224–8.

Masi AT, Hannon JC. Human resting muscle tone (HRMT): narrative introduction and modern concepts. J Body Mov Ther. 2008;12:320–32.

Bottomley J. Quick reference dictionary for physical therapy. 3rd ed. New Jersey: SLACK Incorporated; 2013.

Howley ET. Type of activity: resistance, aerobic and leisure versus occupational physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:S364–9.

Komi PV. Strength and power in sport. In: Encyclopaedia of sports medicine. 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2003.

Wilmore JH, Costill DL. Neuromuscular adaptations to resistance training. Physiology of sport and exercise. 2nd Ed. Chapter 3, USA: Human Kinetics; 1999. 82–111.

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML. The clavien-dindo classification of surgical complications: 5 years’ experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–96.

Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Lee J, Swift SE, Cosson M, Deprest J, et al. An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related to native tissue female pelvic floor surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:515–26.

Basson R, Leiblum S, Brotto L, Derogatis L, Fourcroy J, Fugl-Meyer K, et al. Definitions of women’s sexual dysfunction reconsidered: advocating expansion and revision. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;24:221–9.