Ultrasound has been used in the investigation of pelvic floor disorders since the 1980s. However, the adoption of ultrasound imaging in urogynecology has been slow compared to other subspecialities in gynecology. Nevertheless, due to its ease of access, low cost, safe and non-invasive nature, transperineal/translabial ultrasound has now become the most common diagnostic modality in urogynecology. It allows real time assessment of pelvic floor functional anatomy. 3D/4D imaging further permits access to the axial plane and a comprehensive assessment of the pelvic floor including the levator ani and anal sphincter. The technique has been standardized (Shobeiri et al 2019) and is useful in the evaluation of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse (POP), obstructed defecation (OD), anal incontinence (AI), anal sphincter injuries, and mesh and sling implants. IUGA and its Pelvic Floor Imaging Special Interest Group (SIG) have facilitated education and training of the technique by providing an online ‘cookbook’ of transperineal ultrasound imaging in five different languages and an online course of the method. The SIG further serves as a platform for collaboration with other societies and professional bodies.

Imaging can help assess women suffering from urinary incontinence. e.g., by measuring residual urine volume and assessing bladder neck mobility before placement of a mid-urethral sling. Recent studies using transperineal/translabial imaging to evaluate segmental urethral mobility and urethral kinking have further improved our understanding of the urinary continence mechanism and voiding function. Weakening of mid-urethral support is likely important in the pathogenesis of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urodynamic stress incontinence (USI) (Pirpiris et al 2010). The further the locus of urethral kinking is from the mid-urethra, the more likely USI is (Chen et al 2021). This provides circumstantial evidence for the pressure transmission theory of SUI.

One of the main applications of translabial ultrasound is in the quantification of POP. There is a good correlation between ultrasound and clinical measurements of POP (Dietz et al 2016). Unlike clinical staging systems which are limited to describing surface anatomy, imaging provides information on underlying organs and functional anatomy. A clinical ‘cystocele’ may turn out to be a urethral diverticulum or a vaginal cyst. A clinical ‘rectocele’ may be due to five different anatomical conditions, namely perineal hypermobility, a true rectocele (where there is a diverticulum of the anterior rectal wall into the vagina through a rectovaginal septal defect), an enterocele, a rectoenterocele, or a rectal intussusception (Figure 1) (Dietz & Beer-Gabel 2012). Imaging is required to differentiate these conditions.

Figure 1: Mid sagittal view on Valsalva showing a rectocele (A), an enterocele (B), a rectoenterocele (C) and a rectal intussusception (D). S=symphysis pubis, B=bladder, R=rectocele, A=anal canal, L=levator ani muscle, E=enterocele, Sig=sigmoid colon.

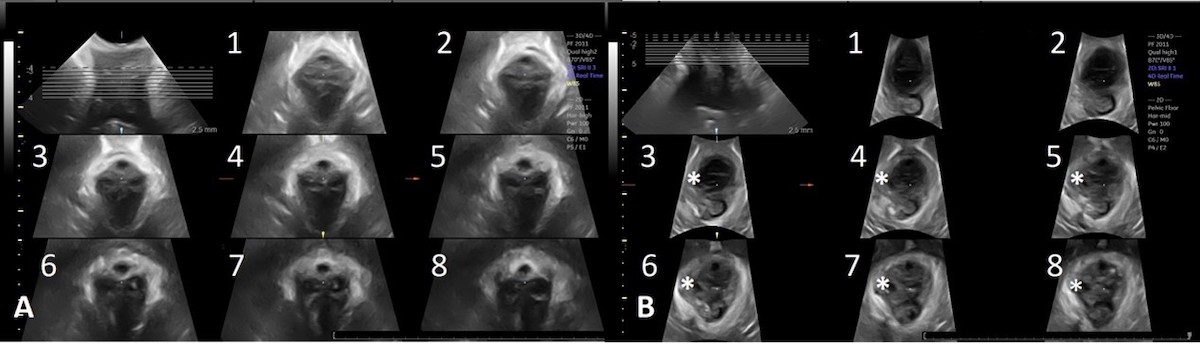

POP can be considered a hernia, with the levator hiatus the hernial portal. Both integrity of the levator ani and the size of the levator hiatus are important in the pathophysiology of POP and are predictors of prolapse recurrence (Handa et al 2019; Friedman et al 2018). Pelvic floor imaging should be part of POP assessment to facilitate patient counseling, surgical planning and in treatment audit. 3D/4D translabial ultrasound allows a direct and reproducible assessment of the levator ani and hiatus. It also facilitates training of the clinical assessment of levator ani by providing immediate visual biofeedback to the examiner (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Tomographic ultrasound imaging of an intact levator (A) and right sided levator avulsion (B). The right sided defect is marked by * in slices 3-8 in Image B.

Obstructed defecation (OD) is highly prevalent in the urogynecological population (Alam et al 2017). OD is associated with a true rectocele and rectal intussusception (Guzman Rojas et al 2016). Surgical cure of rectocele by obliteration of a rectovaginal septal defect is significantly associated with cure of OD symptoms (Guzman Rojas et al 2015). The technique is useful as an initial test in patients with defecatory disorders, commonly avoiding more invasive investigations (Perniola et al 2008).

The standardization of tomographic translabial sonography of the anal sphincter over the last decade has improved repeatability and validity of the method. Transperineal ultrasound is increasingly used to image the anal sphincter (Dietz 2018). Studies comparing exoanal with endoanal sphincter imaging have shown moderate to good agreement between the methods (Daniëlla et al 2012; Ros et al 2017). The exoanal technique is more likely to have a positive impact on clinical practice and research given its wider availability and non-invasive nature.

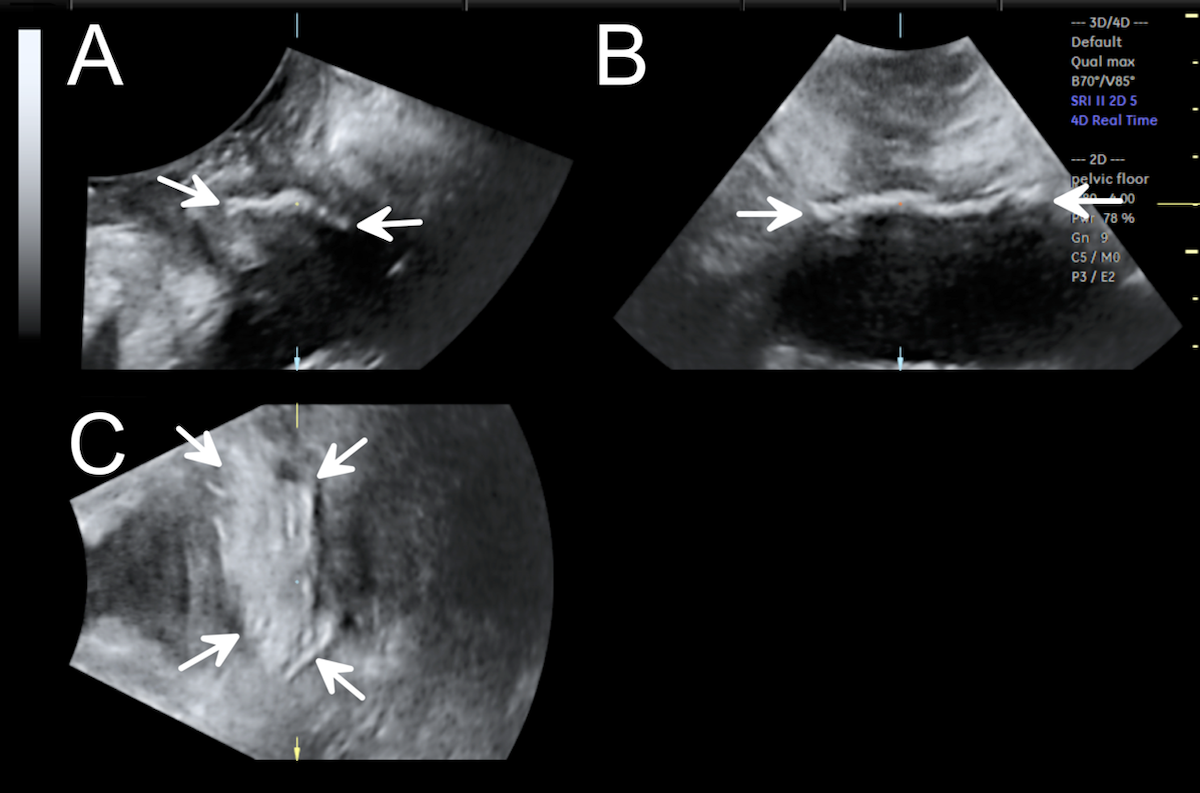

Obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) is the main cause of anal sphincter defects. Exoanal ultrasound imaging can facilitate clinical audit in obstetrics, e.g., as regards quality control after episiotomy (Figure 3) (Subramaniam et al 2015), to determine how accurately major perineal tears are diagnosed (Gillor et al 2020) and the quality of OASI repair (Shek et al 2014). With the capability to diagnose maternal birth trauma by translabial ultrasound, maternal birth trauma will likely become a key performance indicator of maternity services in the near future.

Figure 3: Tomographic ultrasound imaging of a normal anal sphincter (A). Image (B) shows an episiotomy (indicated by arrow). The starting point of the episiotomy was located contralateral to the direction of the episiotomy scar. IAS=internal anal sphincter, EAS= external anal sphincter, A=anal canal.

Bothersome anal incontinence (AI) is not uncommon in the urogynecological population (Guzman Rojas et al 2015). Identification and quantification of AI should become part of any urogynecological assessment. Patients having bothersome symptoms of AI with significant anal sphincter defects on ultrasound should be referred to colorectal specialists for early management.

Transperineal ultrasound is well suited for imaging of meshes and slings as these implants are highly echogenic on ultrasound and the technique allows assessment of the functionality of synthetic implants on Valsalva. It helps determine the presence or absence of synthetic implants (Figure 4), assess the number and type of sling or mesh, location, and course in the pelvis. Imaging should be performed in women with complications, such as recurrent urinary tract infections, voiding difficulties, recurrent urinary incontinence or prolapse, implant erosion into adjacent organs or chronic pain. This is especially the case if revision or removal of synthetic implants is contemplated, to help predict likely functional outcomes after removal, to optimize patient counseling and surgical planning (Shek & Dietz 2021).

Figure 4: A transvaginal mesh in the three orthogonal planes on Valsalva maneuver.

It has taken us several decades to develop the role of ultrasound imaging in pelvic floor medicine. With an additional 5-10 minutes one can perform a comprehensive assessment of the pelvic floor to complement history and clinical examination to aid in diagnosis, patient counseling, and management planning. It is not only useful to practitioners interested in pelvic floor health but also to obstetricians given the increasing awareness of maternal birth trauma.

REFERENCES

Alam P, Guzman Rojas R, Kamisan Atan I, Mann K, Dietz HP. The 'bother' of obstructed defecation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017; 49:394-97.

Chen L, Shek KL, Gillor M, et al. Is location of urethral kinking a confounder of the association between urethral closure pressure and stress urinary incontinence? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021;57:488-92.

Daniëlla M J Oom 1, Rachel L West, W Rudolph Schouten, Anneke B Steensma. Detection of anal sphincter defects in female patients with fecal incontinence: a comparison of 3-dimensional transperineal ultrasound and 2-dimensional endoanal ultrasound. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:646-52.

Dietz HP, Beer-Gabel M. Ultrasound in the investigation of posterior compartment vaginal prolapse and obstructed defecation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2012;40:14-27.

Dietz HP, Kamisan Atan I, Salita A. Association between ICS POP-Q coordinates and translabial ultrasound findings: implications for definition of 'normal pelvic organ support.' Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;47:363-8.

Dietz HP. Exoanal imaging of the anal sphincters. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37(1):263-280.

Friedman T, Eslick GD, Dietz HP. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:13-21.

Gillor M, Shek KL, Dietz HP. How comparable is clinical grading of obstetric anal sphincter injury with that determined by four-dimensional translabial ultrasound? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56: 618-23.

Guzman Rojas R, Kamisan Atan I, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Anal sphincter trauma and anal incontinence in urogynecological patients. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015; 46: 363–366.

Guzman Rojas R, Kamisan Atan I, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Defect-specific rectocele repair: medium-term anatomical, functional and subjective outcomes. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynecol 2015;55:487-92.

Guzman Rojas R, Kamisan Atan I, Shek KL, Dietz HP. The prevalence of abnormal posterior compartment anatomy and its association with obstructed defecation symptoms in urogynecological patients. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:939-44.

Handa VL, Roem J, Blomquist JL, Dietz HP. Pelvic organ prolapse as a function of levator ani avulsion, hiatus size, and strength. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:41.e1-41.e7.

Perniola G, Shek KL, Chong CC, Chew S, Cartmill J, Dietz HP. Defecation proctography and translabial ultrasound in the investigation of defecatory disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;31:567-71.

Pirpiris A, Shek KL, Kay P, Dietz H. Urethral mobility and urinary incontinence. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010;36:507–11.

Ros C, Martınez-Franco E, Wozniak M, et al. Postpartum two- and three-dimensional ultrasound evaluation of anal sphincter complex in women with obstetric anal sphincter injury. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017; 49:508–514.

Shek KL, Guzman-Rojas R, Dietz HP. Residual defects of the external anal sphincter following primary repair: an observational study using transperineal ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44:704-9.

Shek KL, Dietz HP. Ultrasound imaging of slings and meshes in urogynecology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57:526-538.

Shobeiri A BB, Bromley B, Sakhel K, Dietz HP, Chan S. AIUM/IUGA practice parameter for the performance of Urogynecological ultrasound examinations. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:851-64.

Subramaniam N, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Characteristics of episiotomy on translabial ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56 (S1):374.